Moog is pronounced mogue, like rogue. An easy trick to remember this is Dr. Robert Arthur Moog usually had on a roguish smile as he explained things.

He seemed perpetually delighted to show his latest invention to a musician, or to teach the science of sound to a classroom. A grin was never far even when he described what people first thought of his synthesizers in the late 1960s.

“When these sorts of sounds were first being heard by the general public, people were freaking out,” he said in the 2004 documentary Moog. “It was the same sort of reaction that we think of primitive cultures having… that a photographer might steal your spirit!”

Thankfully, the world slowly but surely came to grips with electronic notes. The 1968 classical album Switched-On Bach by composer Wendy Carlos played a big part in this, just as the genius of both Bach and Moog allowed her to usher in a new era of musical possibilities. The impact on every single musical genre was huge.

“We impress upon the children the importance of creative problem-solving, and their own ability to affect change in the world around them through curiosity and discovery.”

In 2006, a year after he passed away, his family and friends created the Bob Moog Foundation. Under the leadership of his daughter, Michelle Moog-Koussa, they preserve the Bob Moog Foundation Archives—a collection of thousands of schematics, photos, catalogues, and even prototypes and vintage instruments. They also run Dr. Bob’s SoundSchool—a 10-week curriculum specifically designed for second graders.

“We aim to teach kids that Bob was a creative thinker who was passionate and committed to building musical instruments,” says Michelle. “We impress upon the children the importance of creative problem-solving, and their own ability to affect change in the world around them through curiosity and discovery.”

The SoundSchool has stirred up the same roguish smiles for over a thousand North Carolinian kids since 2011. Children learn about aural physics, how sound can be synthesized, and how ears perceive sound waves. Some courses are structured around photocopies of Dr. Bob’s own notes. On the Foundation website, Synthesis Fundamentals info posters are also available for anyone interested in the science of sound.

In 2013, his widow, Dr. Ileana Grams-Moog, donated many of Dr. Bob’s papers to Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections at the Cornell University Library. The setback was surprising but did not deter the Bob Moog Foundation Archives from expanding their own collection of historical documents. If anything, it strengthened the non-profit organization’s resolve to create a more comprehensive Archives.

One day, Michelle hopes to fuse together these collections with its SoundSchool into “The Moogseum.” The concept drawings display a multi-million dollar historical facility that would permanently preserve Dr. Bob’s legacy.

“The Moogseum is the end-all vision of the Foundation,” she says. “Its physical manifestation is likely years away due to the massive expense, although we are planning an online Moogseum within the next year or two. Our focus right now is expanding and strengthening the SoundSchool and our historical preservation efforts.”

From 1988 until 2005, Dr. Bob and his family lived near Asheville, North Carolina, where he had previously bought forested acreage. On a recent interview with NPR, Michelle described how the highlands of western North Carolina became her father’s spiritual home. Asheville is where the Moogseum will surely materialize.

Recently Michelle wrote on the foundation’s blog: “When asked on several occasions by interviewers if my father were a musician, he would firmly reply no, that he was a toolmaker, and ‘I make tools for musicians.’”

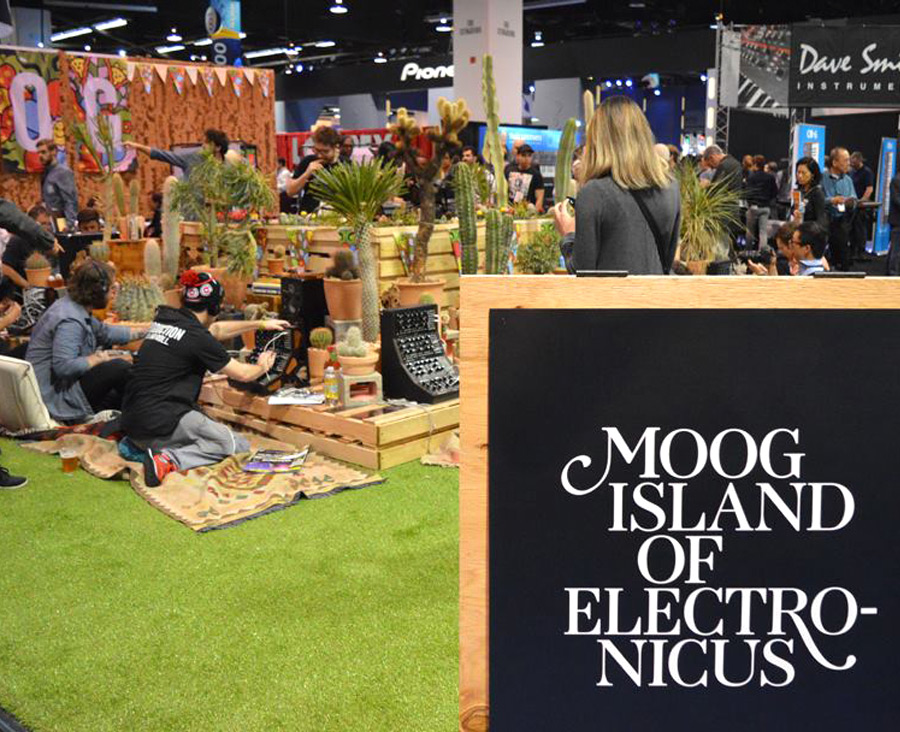

Artists as varied as Stevie Wonder, Gordon Lightfoot, Radiohead, Dr. Dre, Wilco, and The Beastie Boys have all experimented with these tools. Performances by Emerson, Lake & Palmer, The Beatles, and The Doors were among the first to bring the Moog to mainstream music, and even as progressive and psychedelic rock embraced the synth, so did classical and jazz musicians take their own synthesizers to new heights.

Four years ago, the Foundation announced that composer Albert Glinksy would write Moog’s official biography. “Albert is still in the research phase of the book,” says Michelle. “He is an exhaustive researcher.” Glinsky’s biography of Léon Theremin, the inventor of the ethereal instrument, came out in 2000 with a foreword by Dr. Bob.

After graduating in 1957 with two degrees in physics and electrical engineering from two different schools, the 23-year-old Bob Moog began selling DIY theremin kits he had designed. His 1961 “Melodia” theremin, with brand-new transistor technology in its amp, became such a bestseller that he had to take time off his PhD in engineering physics at Cornell to keep up with demand. And so, in the foreword of Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage, Dr. Bob wrote: “I became a designer of electronic musical instruments because of my fascination with the theremin.”

If things work out, as Moog’s smile suggests they will, the next inventor in this cycle of inspiration might just graduate from the SoundSchool. We are all ears.